SOMBALAK

A LOVE STORY ACROSS

THE ARAFURA SEA

A LOVE STORY ACROSS

THE ARAFURA SEA

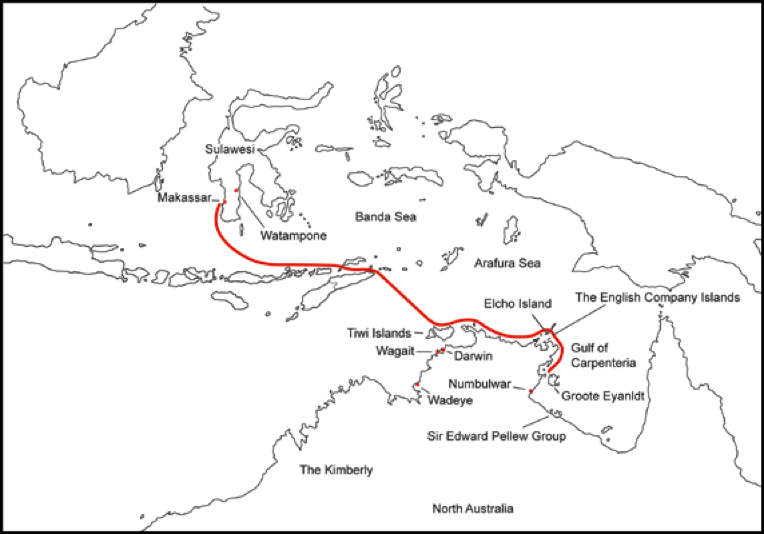

During the trade of trepang until 1907, the Makassans and the Australian Aboriginal people, especially in Marege (a name of Makassans referring to the north Australian coastline), became trading partners and historical family relations. These centuries of encounters are documented through numerous archaeological, historical, social, and cultural customs. From images of boats and sails found in cave paintings in North Australia and Aboriginal bark paintings to songlines (traditional Aboriginal song stories), the legacy is rich. Drawing from these inspirations, we have chosen the word Sombalak for this project, meaning “sail” in the Makassar language. This term is also known as Dhomala, Djomula, or Dhumala in Yolŋu language.

Knowing that there are lots of friendships, sad and happy stories among these people, we have decided to present a love story to celebrate these encounters. A story that can connect everyone, not only between Makassan-Marege but also those who seek the meaning of connection through celebration of common-culture and shared-stories between different nations, highlighting the vibrant interactions and resiliences of certain cultures, and also something that symbolises a profound spiritual connection and transformation, illustrating the enduring bonds that can transcend geographical boundaries. Aimed as a contemporary opera production, Sombalak blends elements of traditional music, dance, and storytelling from both Makassan and Aboriginal Australian cultures. This fusion creates a rich, layered experience of sound and movement that deepens the narrative. The audience is invited to experience the harmonisation of these musical traditions, which not only enhance the storytelling but also celebrate the shared cultural heritage that unites these communities.

Sombalak is an opera that tells the story of the historical trade relationships between Makassan sailors and the First Nations people of Northern Australia from the mid-18th century. Set against the backdrop of cultural exchange and trade in sea cucumber, pearl, and turtle shell, the show follows a Makassan sailor who falls in love with an Indigenous woman. Their love story unfolds amidst the vibrant cultural interactions and shared traditions of the Marege, Bugis, and Makassar peoples. The couple’s journey across the Arafura Sea symbolizes a profound spiritual connection, as they navigate the complexities of their union and the challenges of cultural expectations.

Tragedy strikes when the sailor is lost at sea, leaving the woman to return to Marege with their child, a living embodiment of the fusion between their cultures. Through music and dance, Sombalak celebrates the enduring bonds and shared history between these communities, highlighting themes of love, resilience, and spiritual connection. Our goal is to share this opera with audiences in Australia, Indonesia and beyond, fostering appreciation for the deep cultural ties that unite these regions.

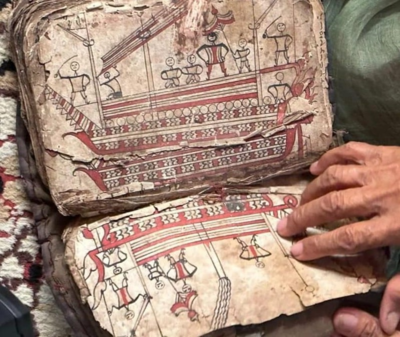

Both Australian Aboriginal and Makassan people are known for their strong spiritual cultures. The Australian Aboriginal people belief is that they are in a constant realm between human to human, human to nature and human to spiritual worlds. Their understanding lies in their daily practices, language system, oral traditions, rituals as well as arts and crafts. In Sulawesi Island, the Bugis or Buginese, is the largest ethnicity in Sulawesi (beside them they have Makassar, Mandar and Toraja and other group ethnicities). The Bugis people are the custodians of I La Galigo, the 14th Century tome recognized the longest recorded manuscript in the world and acclaimed as part of The Memory of the World by UNESCO in 2011.

This document describes the oral history of the Bugis people, with particular emphasis on their poetic and singing traditions and describing numerous rituals that still exist in Sulawesi society. The manuscript defines the inter-relations between human-nature-spirits and, through the journeys of its main character portrays the complexities of human beings and the known universe through stories of travel, love, war and ceremonies in an Odyssean-like epic.

Image of I La Galigo manuscript. Episode of The Beginning of The Middle World. Image by Andi Awaluddin. Manuscript belong to Indo Mosi in Tosora village in Wajo Regency, South Sulawesi

Indo Masse. the latest famous I La Galigo reader in Wajo, South Sulawesi.

In the I La Galigo manuscript, the main character loves to travel but will not journey unless he has his one of the seven special people; tanned-skinned companions with wiry hair, able to speak to animals, to read the stars, who love art and rituals and come from under world (perhaps a reference to the “Land Down Under”?). Certainly, Sombalak’s Makassan producer, through his experiences meeting with modern Yolŋu people, came to the conviction that they were the source of the seven special people identified in I La Galigo.

Among Yolŋu people in Arnhem Land, they have the belief of Bayini, a female spiritual figure who came from north part of their world and arrived in Australia and stayed with them. There they taught the Yolŋu valuable knowledge and eventually became guardian of the land, ocean and the sky. Bayini in Sulawesi language means the woman or wife –and has the same meaning in Yolŋu language. The story of the Seven Sisters is also significant for Australian Aboriginal people as the way they ground themselves through connections with the sky and the land.

A group of Yolŋu dancer and young leader in Elcho Island-Northern Territory doing Bunggul/dance and song about the land

Music plays major role in the Sombalak opera, emphasising the intertwined realms of time and space. Traditional and contemporary music forms from both Aboriginal Australian and Makassan are used. Gurrumul Yunupingu, the phenomenal Yolŋu artist, was a major inspiration for Sombalak and our attempt to bridge the Australian Aboriginal traditional and contemporary music worlds. The deep and thunderous sound of yidaki (didgeridoo) and the sacred beats of bilma (clapstick) meet in the dynamics of the Makassan’s ensemble. The beauty of gandrang (hand-drum), high-pitch flute puik puik, rythmic gong, woods and strings instruments as well as various of manikay, songlines, mantras, chants, ululations, laments and folksongs, all together will be part of the celebration for the re-connection between two cultures, two worlds, two families, and two nations.

Pakarena, a classical Makassar dance performed by masters, Daeng Serang and Daeng Mile in Kalase’rena-Takalar village in South Sulawesi.

In Bugis society, a special group of people called the Bissu holds a unique place. This cis-gendered group is recognized as spiritual leaders with a lifelong dedication to preserving traditional knowledge and serving the people. The Bissu possess a special ability to connect with the spiritual world, bridging the gap between the physical and metaphysical realms. They are also believed to have the power to send and receive messages from spirits. Their shamanistic practices allow them to practice spiritual and medicinal consultations. In the southern Makassar region, there is an oral tradition called Royong where lyrics are taken from old songs and stories, and reinterpreted as lullabies, healing songs, lyrical welcoming, marriage songs and similar occasions, often orchestrated by the Bissu.

The Australian Aboriginal people also have an oral tradition to record their stories through songs, mantras, stories, chants that they identify as Songlines. Their knowledge, values, family lineages, practices, stories of the land, and more, are depicted in their Songlines. The Yolŋu people from Arnhem Land in Northern Territory have many Songlines that connect them to their Makassan relatives. They have special Songlines called Djapana (sunset dreaming) that picture the scenes of the Makassan praus across the horizon, sailing back to Makassar while the Yolŋu stand on the beach waving hands and hope that they will meet again in next seasons. The amount of Djapana songs are countless as each clan/artist has their own interpretation. The Sombalak Project follows the Songlines about Makassan and Yolŋu working together including trade goods, playing cards, paddling canoes or swimming across the ocean waves.

Ardiansyah, a young Bissu, singing a Bissu chant along with Wahyu and Anjelita singing royong

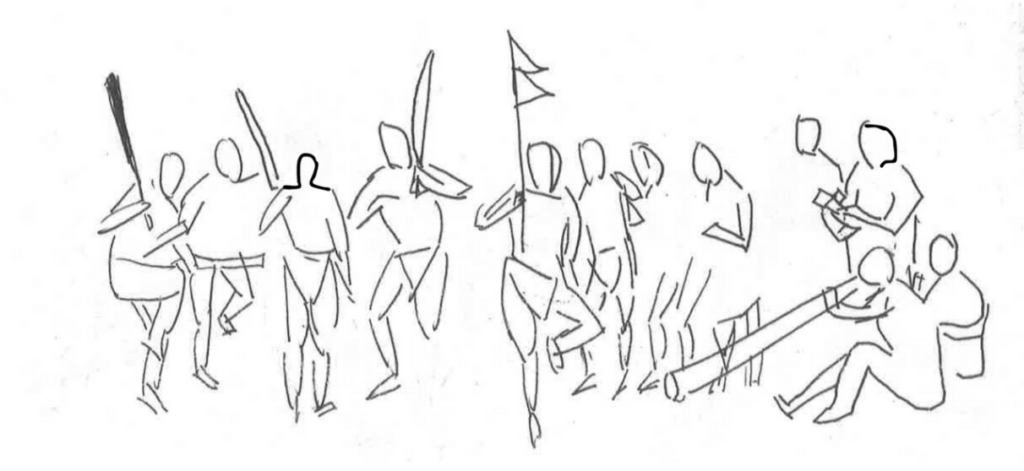

As coastal people, there are lots of commonalities between Makassans and Northern Territory Aboriginals. Some of this commonality is shown in the hand gestures and footwork of dance. The Yolŋu people have gestures that show the scenes of trading, exchanging goods, playing cards, animal hunting or tracing the tracks on the sand. The Makassans use feet stomps on the ground to represent their connections with the spirit, to gain power from the earth and shows bravery and joyful. Women in the Pakarena dance, gently and slightly move their hands, use sliding steps to stay connected with the earth and to stay calm in the midst of the obstacles, contrary to the men who play fast-speed drum, loud voices and flute, to represent the power of the rock standing still in a stormy ocean. A balance of life between strength of men and elegance of women.

With lots of their daily activities near the ocean, the Australian Aboriginal people also display their considerable footwork within dances, especially during the ritual cycle they called Buŋgul. The foot movements articulate their deep connections with the earth using one foot to stand and two feet to parallel move, sliding, jumping, zig-zag, and so on. In both cultures, there is so much richness within the movement of feet that we have included this art form in the Sombalak Project

Manuel Dhurrkay from Skinnyfish’s Salwater Band, showing gestures from his clan with his own song, Lunggurma, the trade wind, during the first stage of the field research and workshop in Makassar.

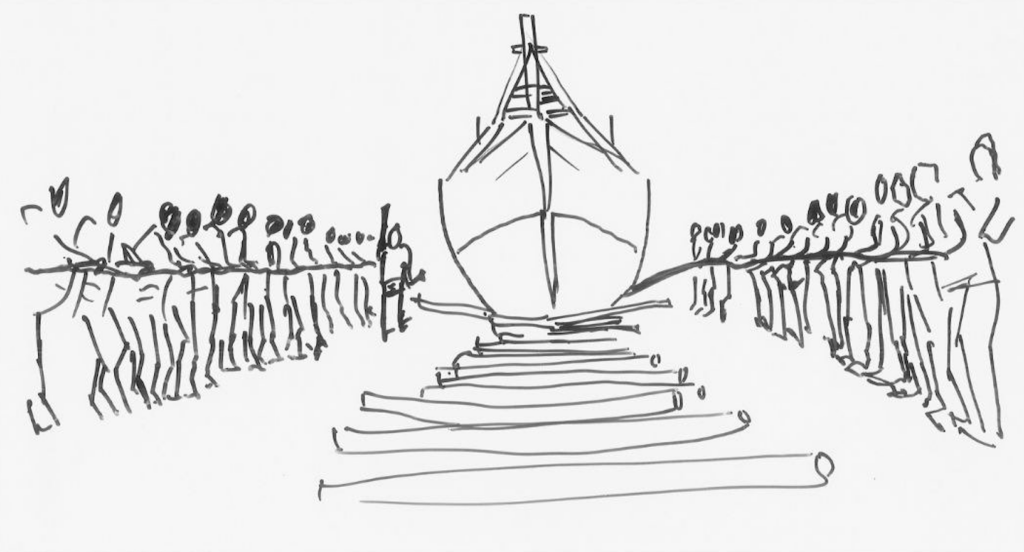

In Makassan culture, houses and boats are often built as representations of human beings. They have structures of skeleton like humans do, an outer skin to protect and beautify and many inner components that give direction and power; both physically and philosophically. In the boat-making tradition, initial rituals are performed to ensure the trees can be easily felled and transformed into a boat. The actual building process requires many spiritual and romantic elements that, like a marriage, is a whole family engagement over the long period of construction. Once the boat is finished, the process of pulling the boat down into the ocean is likened to a mother giving birth. It is not a trivial or menial task but these processes are completed with continuous awareness, persistence, power and prayers.

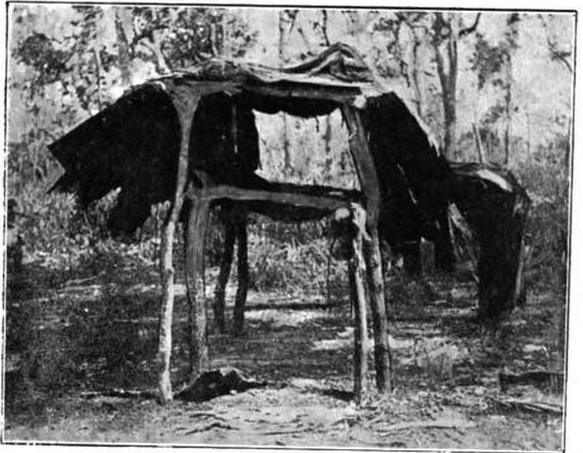

The barkwood shelter by Aboriginal people also reflects their deep understanding of the time and space continuum. While there are few permanent wooden traditional houses in their culture, due to seasonal fire and floods, these temporary constructions reflect and maintain a deep connection with the seasons, climate and the environment.

The stage design for the Sombalak show is largely inspired by the structure of the boat, house and sail with movable and multifunction elements. The wood pillars represent the structure of the house, shelter and the boat. The long bamboo and wooden logs create the movable-foldable sail, big and small and able to be climbed on as well as projected on screen to provide digital visual elements. The performers (musicians and dancers) act as crew members of the prau (boat) and the working, dancing, singing, playing music against these artefacts and motifs becomes a strong, constant part of the stage acts.

Both Makassan and Aboriginal shelter has common structures that made of organic materials from the native plants.

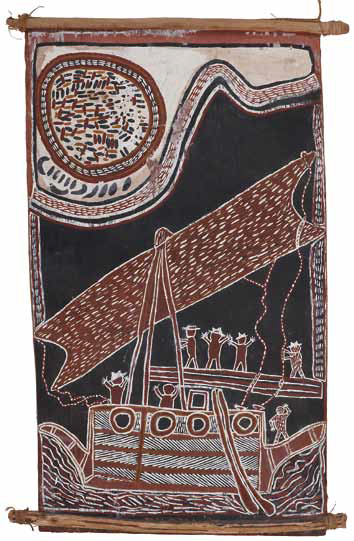

Bark painting is an iconic art work practiced by Northern Australian Aboriginal people. Taken from the stringytree’s bark, flattened and painted with earth pigments and ochres using human hair brush, each clan has their own sacred patterns and each artist has different interpretations. The encounters between Aboriginal people with the outsiders and spiritual realms have famously been put into bark, totem, wood sculpture and cave paintings.Through Sombalak, we have chosen to continue that tradition in modern art forms

The images of the sail and hulls of traditional Makassan boats that were preserved and created by Northern Territory artists include more than just references to their memories of their Makassan friends and families. The Australian Immigration Act in 1901 created massive separations between Australian Aboriginal and Makassan people and the sorrow, sadness and old memories of that time were put into the bark paintings, including the iconic curved-shaped sails along with hundreds of Songlines about the severed relationship.

Bugwanda Mamarika, c. 1970, Makassan Perahu. 77.5 x 50cm

Natural pigments on bark. Museum & Art Gallery Northern Territory, Darwin

Nur Al-Marege. Type of the boat called Perahu Padewakang.

Image by Ridwan Alimuddin. 2018

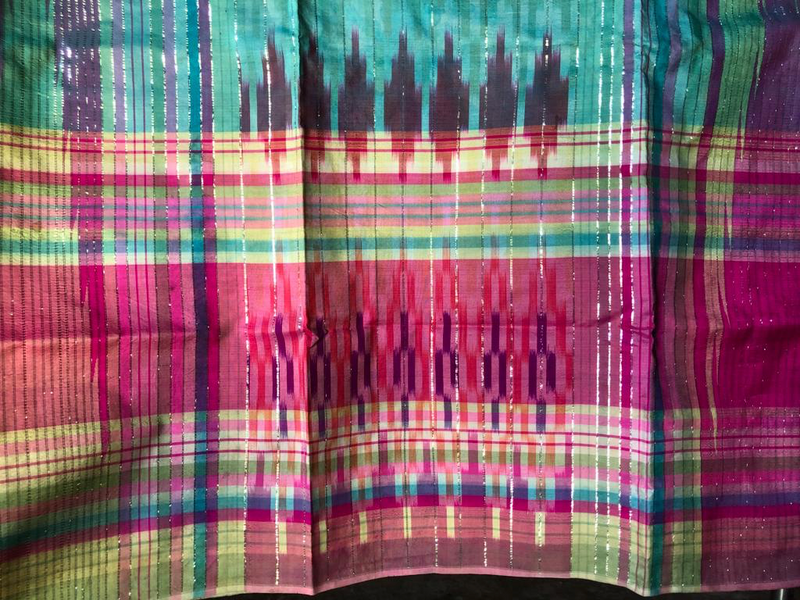

The ancient Aboriginal craft of making mats, baskets, and bags out of Pandanus leaves is still carried out today. A lot of efforts is required, from gathering the materials, mixing the colour ingredients, getting the design right and the final weaving the Pandanus threads. In Indonesia, there is also a strong tradition of hand woven cloth made from nature and the Makassan sail is a fine example of hand-woven material made from palm fibre. Similarly, each tribe has their own story, different colours and patterns to represent their relationship with humans and nature.

Unfortunately, the type of sail that been used for centuries on traditional praus is becoming rare, rapidly being replaced by modern manufactured materials. In defiance of this trend and to honour the traditional methods, Sombalak will use the original cloths, shape-shifted and transformed by local weavers for the scenes.

Gunga or pandanus weaving. Colored only with natural ingredients

Lipa’ Sabbe. hand-woven natural silk sarong.

Private collection Abdi Karya.

Sign language serves as an alternate language for the deaf and hearing people and informally between people of different languages. However, in Australian Aboriginal and Makassan culture it also forms a rich language utilized in dance, ritual, and kinship, often expressing a deep relationship to nature. This sign language plays a vital role in everyday life through gestures, songs, and traditions, contributing significantly to bimodal-bilingual communication. It also serves additional purposes in specific situations, such as during mourning, when holy objects are present, during interactions that require avoiding family members, and in activities like hunting, fishing, or long-distance communication, where silent signaling is essential.

Don Wininba from Elcho Island presenting hand signals for animals during fishing.

Sombalak begins in Makassar, Sulawesi, Indonesia, far from the shores of Marege. Here, a grand spiritual ceremony unfolds on the beach, with bamboo platforms adorned by musicians, artists, and dancers. The Bissu, the Makassan spiritual leaders, bless the gathering with their graceful dances, opening the opera by joining the spirit world, the underworld, and the present. The air pulses with the powerful rhythms of drums, wailing chants, and the harmonious sounds of basing-basing, djolin, and pui pui. In a nearby village, a large sailing boat, or prau, is under construction. The scene is vibrant, alive with energy and celebration, as the boat is prepared for its journey to Marege. The vessel, pulled into the water by sixty hands, sets sail with a ceremonial rooster on board, marking the start of an epic journey.

The voyage across the sea is accompanied by songs and stories of the underworld, recounting the spirits that dwell beneath the waves. As the prau arrives in Marege, the sailors disembark and come ashore in canoes. They join the community in harvesting trepang, a practice rich with tradition, song, and dance. The painted bodies of the local inhabitants, singing to the rhythm of didgeridoo and clapsticks create a harmonious welcome for the visitors.

Some nights later, by the flickering light of a camp fire, a young Makassan sailor meets a beautiful Yolŋu girl. Their attraction is immediate, and over the following weeks, they fall deeply in love. But Yolŋu traditions are binding, and the woman has already been promised to the elders. Negotiations begin, involving a bride price of machetes, knives, cloth, tobacco, and more. In the end, the elders are satisfied and grant her permission to leave and be with her beloved.

Disguised as a man, the woman boards the prau for the journey back to Makassar. On this journey, Sombalak explores the depth of their communication with the sky, spirits, and the ocean, using complex hand signals and the symbolic Sombalak (sail). The sail itself becomes a messenger, carrying meanings of desire and longing between separated lovers. Upon their return to Makassar, the village warmly welcomes the couple. They marry, and the villagers construct a grand bamboo dwelling for them. A festival is arranged, celebrating their union and the cultural fusion they represent.

As the trepang season once again comes around, the prau prepares to sail back to Marege. As there are restrictions on women on Makassan boat, at first the couple feels dismayed by the forced, painful parting.Eventually, they arrange a special ceremony, and are granted permission to travel together on the boat. Though happy and in love, the young woman also feels homesick and rejoices at the chance to return to her homeland and reunite with her Clan. However, the journey proves perilous, and during a particularly stormy night, the storm claims her ill-fated lover overboard. The sea continues to boil and rage, but eventually the unfortunate prau reaches the shores of Marege once again

Back in Marege, a sombre silence falls as the news of the sailor’s death spreads. The Bissu visit the grieving woman, sharing the spirits’ revelation of her husband’s drowning. A mourning ceremony ensues, filled with songs and tears. The prau leaves without her, as she stays with her family, finding solace in the familiar rhythms of trepang gathering and her community. One morning not long afterwards, she wakes up in the dry season to discover she is pregnant. The child, born of the star-crossed love between the Makassan sailor and his Yolgu bride becomes her anchor. For three seasons, she raises the child, joining in the community’s activities, raising the child in her familiar home environment though memories of her husband’s home linger.

Somabalak takes up the story as the child turns three and the community sings and prepares for her journey back to Makassar. The Bissu visit again during this final journey, bringing the revelation that her husband has found spiritual peace and happiness in the afterlife. Despite her loss, she realizes the depth of her love and the happiness it brought her.

On the beach, a final scene unfolds. There is song and dance, with musicians and singers from both cultures celebrating their shared history. The child, now a young boy, embraces both his Marege and Makassan heritage, dancing the dances his father once celebrated.

Sombalak is more than a love story. It is a testament to the enduring bonds between two distant cultures, the spiritual connections that transcend life and death, and the resilience of our people.

The seeds of idea. Abdi Reconnected with his Makassan ancestors through the Makassar jazz festival. After his presentation, Abdi organised a tour for Gurrumul to tell the story of the old Makassar city. Mike Hohnen visited Abdi’s rumata and together found a way to collaborate in the future Sombalak Project.

It took a decade to manifest the collaboration on Sombalak. Skinnyfish Music received the AII grant to start the development. Michael and Abdi started a series of online meetings and research that decided the 1st act should be set in Makassar.

Field research for the Sombalak Project in Makassar involved 12 musicians, 4 dancers, video artist, including Daeng Serang as master of Makassan traditional arts. the major part was at the Fort Somba Opu, the former kingdom of Gowa, where the port of Makassar started the trade of trepang. The team also managed to meet with Australian general consulate at the Pinisi prau for the prolog music festival

Voice recording with female Makassan voices with Makassan diaspora in Victoria at the Auburn Studio, Melbourne

Abdi attended the Garma Festival, where he met three future Aboriginal performers and several female elders. He also visited Elcho Island to interview Don Winimba and receive short lessons in the daily gestures and hand signals of Yolngu sign language, which will be instrumental to the Sombalak Project.

Rehearsals for the work-in-progress presentation. This presentation focused on the opening scenes of the Sombalak opera, set in Makassar, featuring an entirely Makassan cast and characters.

The scene ended up at the arrival in Marege (North Australia) and meet with one Aboriginal person. The team managed to have a 15 minutes live presentation. continued with a two times work-in-progress presentation in Makassar with audiences from AII Board members at afternoon and with audiences from Makassar artists’ collective at evening.

Online meeting for the video/field recording in Elcho Island-NT for the second part of the opera and the Video shots with Yolngu performers on Elcho Island-NT for scenes in Marege.

Michael Hohnen, named NT Australian of the Year in 2013, is an ARIA award-winning musician and producer of several ARIA award-winning albums. However, Michael is perhaps best known for his close personal, musical, and professional partnership with the late, revered Yolngu musician Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu.

Along with business partner Mark Grose, he was a founder of the nationally lauded music label Skinnyfish Music, a company with a distinguished track record producing musical projects with Aboriginal bands and their communities across the Territory.

A graduate of Melbourne’s VCA, and with a musical career spanning over thirty years, during the late 80’s early 90’s Michael toured Europe with both a Chamber string orchestra and pop band ‘The Killjoys, and since then has toured Australia, Europe and Asia multiple times as a musical director, a producer, and a musician. He has worked with Sarah Blasko, Delta Goodrem, Kuya James, Caiti Baker, Tasman Keith, Ego Lemos, Tom E. Lewis, Briggs, and the late Ross Hannaford, and has performed.

Michael and Gurrumul conceived and produced Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow), Gurrumul’s final studio album. This became an astounding musical and critical achievement, combining traditional Yolngu songlines and harmonised chants with dynamic and hypnotic orchestral arrangements by composer Erkki Veltheim and interpreted by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra and Sydney Symphony Orchestra. /p>

In 2018, the album debuted at number one on the ARIA charts, earned seven ARIA Award nominations, and won four. Michael served as the musical director for the theatrical adaptation of the album, Bunggul, which Don Wininba Ganambarr and the esteemed theatre producer Nigel Jamieson co-directed.

Six major Australian festivals funded the event, which opened to sell-out shows at the Sydney, Perth, and Adelaide Festivals. Unfortunately, COVID forced the postponement of the Melbourne, Darwin, and Brisbane festival seasons.

Don is a senior Yolŋu man from Galiwin’ku and Gurrumul’s brother-in-law. His status is that of a cultural leader, also known as Djungaya. In that role he has responsibility for cultural and family matters for some clans in North East Arnhem Land.

The Makassan people took his grandmother, and she eventually passed away in Makassar. In the 1980s Don travelled there to see the burial site.

Don was elected as one of the first councillors for the East Arnhem Shire Council (Gumurr Marthakal Ward region) during the inaugural elections in East Arnhem.st Arnhem, NT, in October 2008. His duties included representing the interests of all the region’s residents, providing leadership and guidance, and participating in the council’s deliberations and community activities.

From 2019 – 2023, Don co-directed Buŋgul, based on Gurrumul’s posthumously released album, Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow). Receiving glowing reviews in most major Australian cities and festivals, Buŋgul allowed audiences to immerse themselves in Yolŋu music and dance combined with Europe’s musical tradition.

Abdi is a performing art artist and cultural programmer from Makassar. He presented his works and featurings at interdisciplinary forums at the Watermill Center-New York, the Guggenheim Museum New York, the International Theatre Festival in Colombo-Sri Lanka, the Ubud Writers & Readers Festival, the Makassar International Writers Festival, the Jakarta-Jogja-Makassar Biennale, the Castlemaine State Festival, The Rising Festival Melbourne and Indonesian Dance Festival.

He has been developing a series of collaboration with Yolŋu people in Northern Territory-Australia since 2014 and managed to produce Yolŋu-Macassan exhibition 2017 in Makassar, Yolŋu-Macassan Project at the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial-QAGOMA-Brisbane, SalamFest 2023 in Melbourne and then Garma Festival 2023-2024.

He is a founding member of Marege Institute, a collective of artists-scholars-enthusiast of the narrative around the Australia-Indonesia historical relationship through the history of the trade of Trepang